Navigating an NJ Tube Trial for an Interstage Heart Baby

To set the scene for you: my daughter’s second open-heart surgery was canceled, she was interstage in heart failure, losing weight and we needed to buy more time. After conferencing with several doctors, we decided to try an NJ tube. For the previous 6 months, we fed her through an NG feeding tube but this was no longer working out so well.

In this post, I’ll explain an NJ tube, why someone may need one, how it’s inserted, how feeding works, and our experiences. When considering this trial, I struggled to find information on others’ NJ experiences, so I hope this can help another parent navigate this decision and journey.

No time to read right now? Pin it or email it to yourself for later!

NJ Tube Basics

What is an NJ tube?

An NJ tube or Nasojejunal Tube is a type of feeding tube that goes from the nose (naso) to the second part of the small intestine (jejunum).

The jejunum’s main function is to absorb important nutrients.

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine, the jejunum is the middle section, and the ileum is the last section.

What’s the difference between an NG, ND, and NJ tube?

NG (Naso-Gastric), ND (Naso-Duodenum), and NJ (Naso-Jejunal) tubes are typically the same feeding tube product, with the same look and parts. However, the insertion process, placement location, and use case differ.

NG tubes go from the patient’s nose to their stomach. ND tubes, go from the nose to the first part of the small intestine (duodenum). NJ tubes, go from the nose to the second part of the small intestine (jejunum).

Nutrition, formula, milk, and medications pushed through an NG tube drop into the person’s stomach. However, for ND/NJ tubes, contents are dropped into the small intestine.

A nurse, caregiver, parent, or anyone trained to place an NG tube should be able to insert it anywhere at any time without special tools. Select hospitals require an x-ray post-insertion to confirm placement.

Only a trained medical clinician can place ND/NJ tubes due to the complexity of navigating through the stomach and small intestine which requires some imaging or visual aid tool.

PLEASE NOTE: Only attempt to insert a feeding tube if you have been directed to and received proper training by your child’s medical team. Improper insertion can cause injury and damage.

What’s the difference between an NJ tube, a J-tube, and a GJ tube?

An NJ tube is a nasal feeding tube that is inserted through the nose, down the esophagus, through the stomach and ends in the small intestine. Part of the tube hangs outside the patient’s nose, taped to the face, and the other part stays down inside the patient’s body ending in their small intestine.

A J (Jejunostomy) tube is a type of feeding tube that is surgically inserted through the belly with only the port on the outside of the person’s body, and the other end of the tube stays inside the patient’s body, in their small intestine. It is very similar to a G-tube, however, the JT’s access point is to the small intestine versus a GT’s access to the stomach.

A GJ (Gastro-Jejunal) tube is a gastric feeding tube that is surgically inserted through the belly so only the ports are on the outside of the patient’s body, and the other part is inside the patient’s body, in the stomach with an additional tubing through to their small intestine. A GJ tube can allow greater flexibility offering options to push medication into the gastric port, ventilate from the gastric port, and push nutrition into the jejunum port.

All NJ tubes, J tubes, and GJ tubes end in the jejunum (small intestine) so the tubie’s nutrition and food can bypass the stomach and be delivered directly to the intestine. However, a GJ offers an access point to the stomach, in addition to the intestine, whereas the NJ and J only provide access to the intestine.

Reasons for the tube

Why might someone require an NJ tube?

There are numerous reasons someone may require an NJ feeding tube, such as due to gastroparesis (or delayed gastric emptying), severe GERD, pyloric stenosis, or severe pancreatitis.

Placing an NJ is an easier process than surgery for a G or G-J tube, so if time is of the essence, an NJ might help.

A hospital may require a baby to be a certain weight before they will allow a G-tube or GJ tube surgery, and therefore an NJ could help bridge the gap for a need temporarily.

Some may want to test an NJ to try understand their feeding, digestion, or absorption issues.

There are hundreds of reasons someone could need to use a feeding tube. NJ tubes are less common than NG and G tubes but are helpful for select cases.

Our Tube Feeding Journey up to this point

My daughter was reliant on a nasogastric (NG) tube shortly after birth. She was born critically ill and required open heart surgery at 3 days old. This caused a paralyzed vocal cord which impacted her ability to nurse or bottle feed. Instead, she needed a feeding tube to eat safely and to gain weight.

She wasn’t gaining weight in her first month, so we had to make some medication and nutrition changes. Finally, though, we got her moving in the right direction using an NG tube.

Her surgical hospital trained us in NG tube feeding at home. They offered this so we could take her home instead of staying in the hospital longer only for feeding challenges.

Now she was in interstage, one open heart surgery down, awaiting another planned repair. To get to this second surgery and have a higher chance of a better repair and smoother recovery, she needed to gain weight.

For the following 4 months, she gained weight. NG tube feeding came with various challenges, vomiting being one of them. At first, it wasn’t so much, but over time it increased excessively.

As she slipped further into heart failure, and her heart was working extra hard, she struggled again to gain weight. Her weight stayed stagnant, and then she started losing weight.

Panic! This wasn’t okay.

We needed her to gain as much as possible in preparation for her second open heart surgery, a big complex repair. I can’t properly explain the amount her cardiologists and surgeons stressed this. This pressure ruled our lives.

NJ Trial Decision

We regularly had gastroenterologist, cardiology/nutrition team, feeding therapist, and cardiologist appointments. Weight gain, intricately linked with feeding, was often the central topic of these appointments.

Her surgical team decided to delay her second open heart surgery to gather more information, make a better plan, and, ideally, get her to gain a bit more weight.

Babies with congenital heart defects often struggle to gain weight. My daughter was no different, this was a challenge from the start. And at this point with her heart struggling even more, extra weight gain was an extra tall order.

Still, I pushed and tried everything possible. Heart medications? Check. Stomach medications? Check. Probiotics? Check. Slowing down her feeds? Check. Speeding up her feeds? Check. Increasing the volume? Check. Decreasing the volume? Check. Adjusting the schedule? Check. Changing the insertion depth of the tube? Check. Holding her (or not) in specific positions. Check.

It wasn’t enough and we were out of options. Losing weight was not an option.

We needed to reverse the weight loss and, at a minimum, maintain her current weight. Ideally, she needed to gain more.

Her team diagnosed her with severe GERD. And they were also treating her for gastroparesis (delayed gastric emptying). However, we did not put her through proper tests to verify the diagnosis. It wasn’t the time to do this. Her heart had to come first, and later we would address other things.

Her cardiologists on both coasts conferenced and discussed. Collectively, we all decided to trial an NJ tube to see if it would make a difference for her.

Based on her symptoms, medications, and the timeline, at this point, her team did not believe a G-tube would help.

The Process

NJ Tube Insertion

An NJ must be inserted at the hospital by a clinician. Depending on the hospital’s setup and processes, it could be done bedside or in imaging or radiology.

The first step is easy, like inserting an NG tube, through the nose, down the esophagus, and into the stomach.

The second step, however, is more complicated and requires a look inside.

Directing the tube through the stomach and to the right section of the small intestine is tricky. They need to use some imaging or visual aid.

The clinician might use fluoroscopy (like a continuous x-ray video, not only a single image), or an endoscope (a tiny tube with a camera on the end). Avanos also makes a special device, CORTRAK, to assist in tube placement.

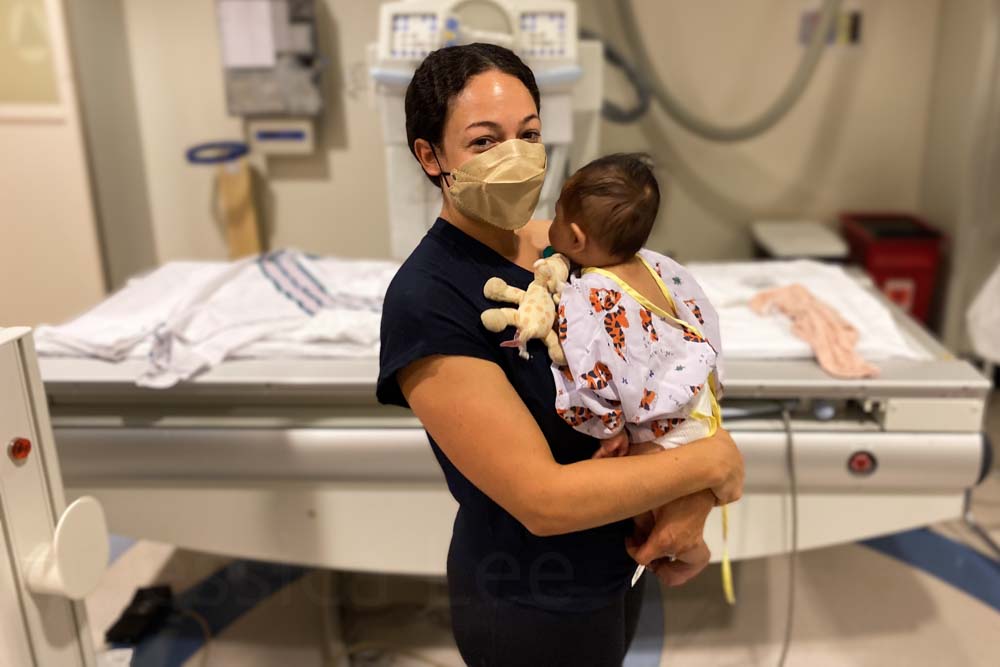

We brought our daughter into radiology at the children’s hospital. After waiting, they took us into an x-ray room. They explained the plan, showed us the supplies, and had us change her into a hospital gown.

Tiny hospital gowns look so cute and feel so wrong.

For the insertion, they had us leave and told us to return in 20 minutes. It only takes approximately 10 minutes, but they added a buffer for setup and cleanup.

It was difficult to leave, and it probably would have been even more difficult to stay.

She was awake for the procedure. The team said it’s uncomfortable, but shouldn’t be painful. I’m not sure how much I believe this. In some cases, they use sedation but they didn’t for ours.

Walking back hurt my heart as we heard her screaming like crazy.

Recovery

As she stretched her arms out to us, she collapsed onto us and passed out, sleeping most of the rest of the day and night. We call them trauma naps.

It’s awful to witness your baby go through such difficult situations that aren’t fair.

Unfortunately, the same day she still vomited, but this time it was alarmingly brown and tinged with red. Her team reassured us this was okay and likely some blood from the insertion process. It wasn’t supposed to hurt! Cue the mom guilt.

Thankfully, the next day, she seemed okay. She did not seem bothered by the NJ tube even though it had a bridle which I (later) heard can be extremely uncomfortable, even painful. More mom guilt.

While she seemed unbothered by the tube itself, I did notice her oral aversion kicked up exponentially. Before this, it had been inching up, but this seemed to tip her over the edge. She was gnawing on her fingers, pacifier, or toys, but would not let me, a bottle or anything I introduced anywhere near her mouth.

NJ Tube Feeding at Home

Feeding Changes

Earlier, we were doing bolus feeds with her NG tube. Switching to the nasojejunal tube meant we had to switch to continuous feeds. We changed from feeding her every 3 hours to feeding for 24 hours continuously.

Previously she was fed 80ml over 45 minutes every 3 hours. Now with the NJ, I had to set her feeding pump to slowly drip all of her day’s milk into her intestine over 24 hours.

One drop at a time all day long. While she was awake, and while she was asleep. Yes, while she was in the car and while she was in the bath.

Logistical Challenges

Being on 24-hour continuous feeds meant she was always connected to her feeding pump. Moving about the house was logistically challenging.

Trying to care for her typical and medical baby needs under this new normal, along with her brothers’ regular needs was trying. Leaving the house was even more of a to-do.

I had to make sure she was close enough to an outlet to keep her pump plugged in for part of the day. The battery would only last for slightly over half a day. We couldn’t have her feeding pump run out of battery.

We got a backpack from DME which offered greater flexibility for moving around with her always connected. It fit her pump, tubing, some supplies with a little extra space to spare in the backpack.

I would sling it over my back whenever I needed to move her and set it down, or hang it up wherever nearby. Of course, she found this was a great time to start rolling and kept getting tangled up in her tubing.

Additionally, I had to find a way to keep her milk cold enough, at a safe temperature. She needed enough in her feeding bag so that it would never run out. But it had to be kept cold (in a Southern California summer) so that it wouldn’t spoil.

Emotional and Physical Challenges

Going through this was lonely and complicated. I didn’t find anyone to talk to about the NJ experience specifically.

Certain things were confusing and I couldn’t get clarity. Some of her medications were supposed to be given with her milk. But others were supposed to be given on an empty stomach. She was always being fed, but the tube was bypassing her stomach. So was it always empty?

There wasn’t a chance she would take her medications orally. So was it okay that they were now going through her tube directly to her intestine rather than in her stomach? At the same exact dosage?

Support was lacking. Little information or guidance was provided about the NJ tube.

For her NG tube, we watched videos, nurses, and demonstrations and completed hands-on training. I was able to confidently care for her tube at home, and replace it whenever necessary.

For an NJ, you cannot replace it at home, which makes sense. But this also made our feeding journey more complicated. To get a new one, we would have to return to the hospital.

Since it is more complicated to place an NJ, they added a bridle to lower the chance of her pulling it out. Additionally, there was a piece of medical tape on her cheek like for an NG. At home, I still used my cute feeding tube tape for her NJ.

A bridle is a small flexible silicone tube that is looped around the nasal bone through both nostrils and clipped on the outside to help secure a nasal feeding tube. They did not ask or share details about the bridle with us. Unfortunately, later I learned bridles can be quite painful. While they work in some cases, others do not recommend them.

We got this new tube to try to address her vomiting and weight gain struggle. While she was vomiting less, it didn’t stop completely. Now instead of vomiting up milk, she was vomiting up a rainbow. This scared me more.

Did the tube change work?

Ultimately, no, it didn’t help in my daughter’s case. Yes, it helped lessen her vomiting. No, it did not reduce it enough to suggest this was a solve for her stomach problems.

Of course, every case is unique and NJ tubes are an important option for some.

We gained some information about her feeding challenges and vomiting, which was helpful in a way.

But I do not think it was worth the trauma and associated effects of getting the NJ tube. I wish she didn’t have to go through that.

Switching back to NG

One night, one of her medications clogged the tube. This was not a rare occurrence, but unfortunately, this was an extra stubborn clog. I tried all the tube unclogging tips, but it was a goner. The tube ended up splitting, and I had to pull it out.

I removed her NJ tube after only 1 week, and I reinserted a new NG tube.

From the NJ routine, we adopted the feeding schedule. Instead of returning to bolus feeds, we kept her on continuous feeds. Initially, this lessened her vomiting.

Thankfully we got her to slowly gain a little more weight.

Closing

An NJT or Nasojejunal Tube is a feeding tube that is inserted in the patient’s nose and ends in the middle of the small intestine. There are various reasons someone could need this tube to address digestion, absorption, or other gastric issues.

We tested an NJ for my daughter for 1 week. The insertion was done in the hospital and was a bit traumatic, and I wish she hadn’t gone through that. Switching from NG to NJ feeding came with some adjustments and new challenges. We learned from the trial, but it did not resolve her issues enough to justify continuing with the NJ tube.