Lines and Tubes and Beeps, oh My!: A Baby After Open Heart Surgery

Lions and tigers and bears, oh my! What’s the equally alarming, open heart surgery version? Lines and tubes and beeps, oh my!

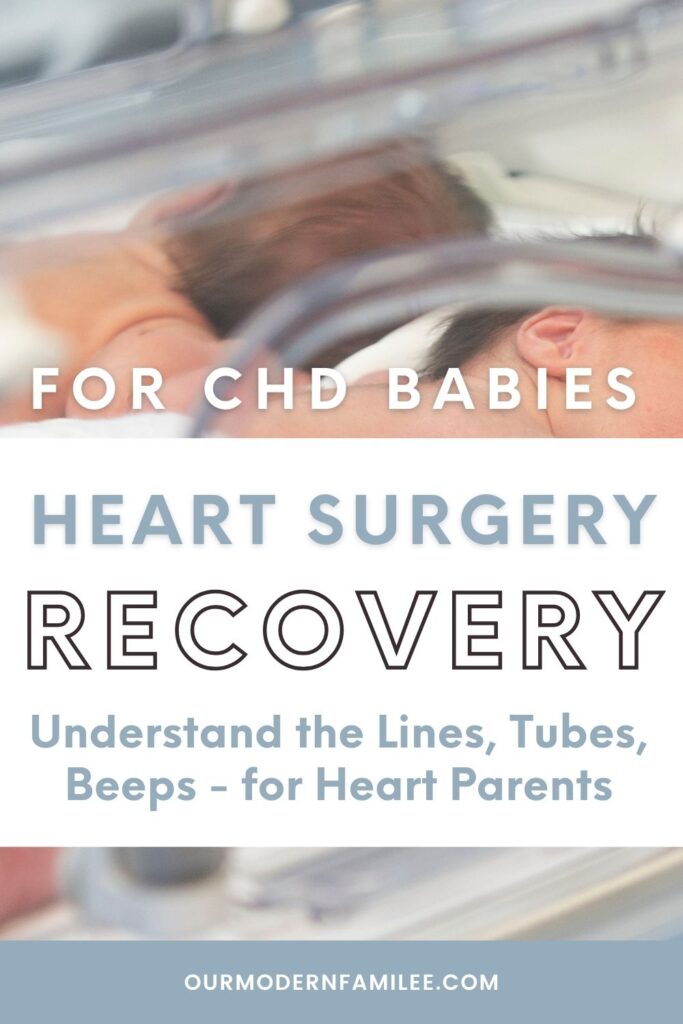

We’re discussing the various wires, tubes, lines, machines, beeps, and more that you might see in the cardiac intensive care unit attached to your baby after open heart surgery.

Use this guide to help prepare and understand what will support your child’s recovery and why they need these wires, tubes, and equipment. Let’s dive into what lines to expect immediately post-op from your child’s heart surgery.

Jump to: Why, Lines, Tubes, Beeps, Dropping lines, Scars

No time to read right now? Pin it or email it to yourself for later!

Our Tangled Tubes

From 25 weeks pregnant, I knew my infant daughter would require open heart surgery. I dove into learning everything I could, and I found pictures of babies in recovery after open-heart surgery.

I read that as a suggestion, you should look at photos to try to prepare yourself. It helped me, and it was impossible to be 100% prepared. I don’t think it’s possible to be fully prepared to see your child in this state.

Everything is different when it’s your own baby.

Our reality was even further removed than imagined. My daughter was born in critical condition and needed open-heart surgery imminently instead of being able to wait several months as originally thought.

So I saw my daughter at only 72 hours old, exactly 3 days from her birth, already covered in a mess of lines, tubes, and wires. It seemed to all be taking over her tiny 6 lb. body. We could barely see much of her underneath it all.

She remained in the cardiac intensive care unit for 2.5 weeks, having to navigate some hiccups during her recovery. She maintained many lines here.

Then she went to the step-down unit for another 1.5 weeks, shedding most of her lines, before we got to take her home.

Though even once at home, she kept one of her tubes for many more months. She sported a tube coming out of her nose, an NG tube, for over half of her first year. This was not the feeding journey I anticipated, but it helped us bridge an important gap.

Later on, at 6.5 months old, we took her to another children’s hospital for her second scheduled open-heart surgery. Thankfully her recovery went more smoothly this time around.

After her first time, I became familiar with all her lines and tubes. So for this second time, it wasn’t as shocking seeing it all. Still, it’s not easy.

Since her recovery was easier though, she was able to shed many of her lines more quickly than her first recovery.

Why are all of these necessary?

Open heart surgery is invasive and involved. It requires significant care, attention, and support – both from medical professionals and from medical technology.

Some of the lines and tubes help support the heart patient pre-op, some during the actual surgery, post-op, or even some combination of these events.

They all have a different purpose, either to support the patient or help inform the doctors and nurses of pertinent health information. The lines and wires may look scary at first, but they are there to help support your child.

DISCLAIMER: The information provided on this blog is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered as professional advice. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your or your child’s physician or other qualified health provider with any question you may have regarding a medical condition. The author of this blog is not a doctor or a medical professional. The views expressed on this blog are based on personal experiences, research and general knowledge. Any reliance you place on the information from this blog is at your own risk. While every effort is made to provide accurate and up-to-date information, the author makes no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability of the information contained on this blog for any purpose.

Open Heart Surgery Lines, Tubes, Beeps, Monitors, and Machines for Parents to Understand

To help prepare me for my daughter’s open heart surgery, I gathered questions to ask the heart surgeons, talked to other heart moms, and looked at photos of CHD warriors right after open heart surgery.

The first time, as a brand new heart mom, is harder, even if you know what to expect, in theory from reading and talking with others, it’s still always different in person, when it’s your reality.

Seeing your baby covered in an abundance of lines, wires, and tubes is a lot to handle.

I think with a little reframing, however, you can find a way to accept the lines. It may never be easy, but hopefully, this guide can make it slightly more palatable.

Information is knowledge, and knowledge is power. When you understand more, it can empower you to accept the difficult situation and better advocate for your heart warrior.

Let me take you through the typical lines, tubes, and beeps you may encounter post-op in the cardiac ICU on or around your baby after open heart surgery.

Lines

Arterial line

An arterial line, also known as an Art Line or A-Line, is a thin catheter tube that is placed in an artery to provide continual blood pressure readings.

Art lines are placed during open heart surgery and used during ICU recovery. Typically they’re placed in the wrist, but could be placed elsewhere in the arm, foot, or groin.

Atrial Lines

The left atrial line, or LA line, is another type of catheter that’s placed in the heart to measure pressure in the left atrium.

The right atrial line, or RA line, is meant to measure pressure in the right atrium.

Blood Pressure Cuff

Your baby may be sporting the smallest blood pressure cuff you’ve ever seen. Their arterial line gives ongoing blood pressure readings, but often they will keep a blood pressure cuff on a baby post-op or put it on intermittently to gather additional readings.

Central Line

A Central Line, or Central Venous Catheter, is a long thin tiny tube that is inserted into a patient’s vein through to their heart used to deliver medicine, nutrition, or other fluids to a patient more quickly. It can also be used to draw blood instead of separate individual pokes.

Central lines can be inserted in various places, but are commonly inserted in a patient’s neck, thigh, or arm. This type of line is sturdier, can offer more connection ports, and can stay in place longer than a standard IV.

They are used for open-heart surgery and during the recovery period in the intensive care unit. Central lines allow physicians and nurses to deliver critical medications, and fluids, and draw blood to get a read on a patient’s recovery health.

Heart Leads

Heart leads, or ECG or EKG leads, are small electrode stickers attached to wires. These leads attach to an electrocardiogram machine to give readings on the heart’s electrical system.

Different brands of medical equipment have slightly different setups and approaches to the leads and electrodes.

CHD kids become familiar with heart leads as they regularly have electrocardiogram tests during cardiologist appointments, and during any trips to the hospital.

For my daughter, they kept 4 heart leads on her throughout her entire hospital stay as they always required certain readings. These leads were typically switched out for new ones daily.

Additionally, when performing an EKG, they would, temporarily, attach a full set of electrodes (she had 10 as a baby) to perform the test.

IV

A standard intravenous line, or peripheral IV catheter, is a thin and flexible tube that can be inserted into a vein, often in your hand, to deliver medicine or fluids, or to draw blood. This is likely the one you are most familiar with, as it is the most common one used in a hospital setting.

Heart babies may have IVs for short-term needs, but not often for longer-term use.

For certain busy babies at particularly active ages, they may use soft restraints. These are soft, flexible fabric covers that usually velcro close. They’ll wrap it around your little one’s forearm or calf to hold their IVs and other lines in place to try to disable the baby from pulling on them.

NIRS Monitor

Your baby may have this forehead monitor sticker thing, sometimes a single one and others could need 2, one for the left and one for the right side.

This sticker uses near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) which is a non-invasive monitoring system that estimates cerebral (brain) oxygenation. This provides another data point, another check for brain-related injuries.

Pacing Wires

Temporary pacing wires are tiny thin wires placed during open heart surgery that go from the heart to the outside of the body, usually by the abdomen. They are kept in place usually for a couple of days, at least, or longer if needed.

A patient’s heart rhythm can be off after their surgery, sometimes it needs a little time to recover and settle into its new rhythm and flow.

Your child’s medical team can attach the pacing wires to an external pacemaker box that will help their heart keep a specific tempo if the team finds it necessary. Or, the wires may never be used but are there for a just-in-case scenario.

These temporary pacing wires are different than permanent pacing wires attached to an implanted pacemaker.

PICC Line

A PICC Line, or Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter, is a type of Central Line.

My daughter got a PICC line placed at 1 day old. They put it in her thigh because they were having trouble drawing enough blood from her IVs, and they needed to start a continuous intravenous medication until her surgery.

Her PICC stayed in for 20 days. She also had a Central Line placed during her surgery in her neck because they needed additional access points, the PICC alone was not enough.

Pulse Oximeter

A pulse oximeter is a small device used to measure the amount of oxygen in someone’s blood. This can give a quick read on how well someone is breathing and whether they might need more or different support.

Heart babies need pulse ox readings regularly. This is a standard test during pediatric cardiology appointments, and if a heart baby is in the hospital. Some critical CHD babies also need to do regular oxygen saturation reads at home.

You have likely had a pulse ox reading before at a doctor’s appointment using a small device that clipped onto your fingertip.

For babies, they use a small flexible tape with a sensor and wrap it around the baby’s foot, toe, or sometimes finger. The sensor is connected to a wire connected to the machine that does the reading.

Sternum Wires

Sternum wires, or sternal wires, are wires made from stainless steel or titanium used to hold the sternum together from a sternotomy after open heart surgery to aid in the healing process.

These are internal, you won’t see them on your baby externally, but you might notice them on a chest x-ray.

Tubes

Breathing Tube

When a patient is intubated for open heart surgery, they need a breathing tube. This isn’t really a single tube, but a group of tubes to support intubation and ventilator breathing.

The endotracheal tube is a tube placed through a patient’s nose or mouth down their windpipe, or trachea.

This endotracheal tube is connected to a ventilator with additional tubes. There is a tube that delivers oxygen to the patient, breathe in, and another tube for CO2 release, breathe out.

For open-heart surgery, a baby is intubated. Sometimes a baby may be extubated in the operating room at the end of their surgery, but if not, they will be extubated in the ICU when their team decides they’re ready.

Chest Tube

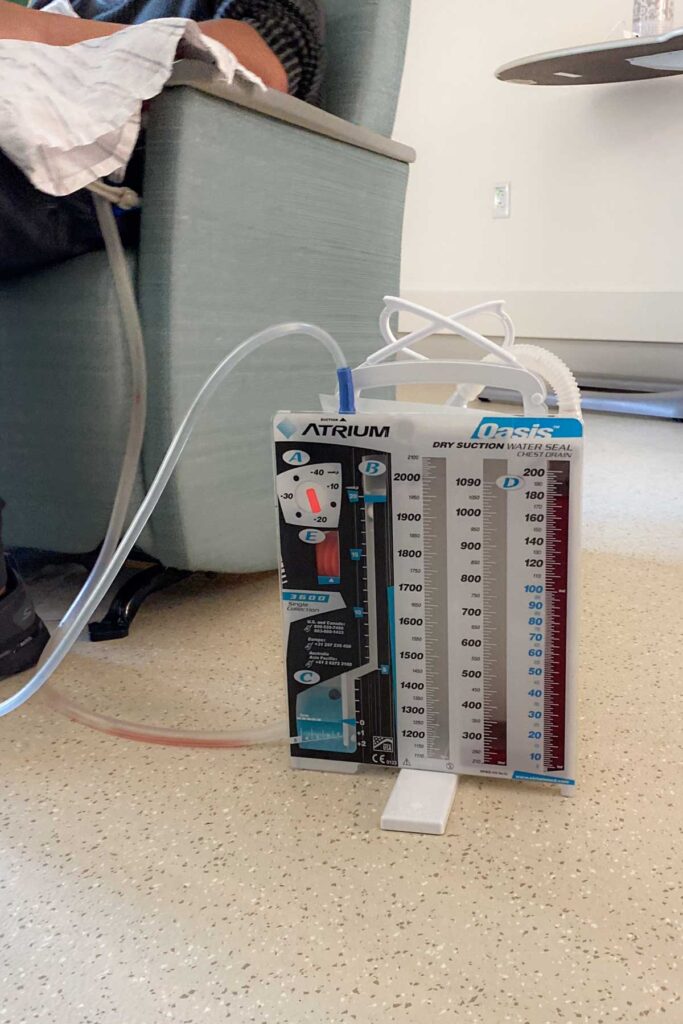

A chest tube, sometimes called a drainage tube (though there can also be other types of drainage tubes), is a thick clear plastic tube that is placed during open-heart surgery near the sternum to drain blood from around the heart and lungs.

Unfortunately, this tube is known to be very uncomfortable and can cause pain. It is extremely important, however, and must remain in place until the medical team decides it’s okay to remove.

For some babies, they can have their chest tube removed within a couple of days post-op, while others may need to keep it in longer. Depending on the surgery, a baby may have a single chest tube, or two, or even three.

Feeding Tube

A feeding tube is a tube used to feed someone when feeding by mouth is not possible either temporarily or permanently. There are different types of feeding tubes, and some are used short term, like after surgery, for a few months, or some are used ongoing for specific needs.

If a CHD baby does not already have a feeding tube, then usually, their medical team will place an NG tube for use shortly after surgery. If they have no feeding trouble, then this can be removed quickly.

Foley Catheter

A foley catheter is a tube, or catheter, that is placed in the bladder to drain urine from the body when a patient is unable to urinate.

Nasal cannula

A nasal cannula is plastic tubing that goes partially into the nose to deliver oxygen to a patient.

The more common nasal cannula is for low flow oxygen, and a slightly different version is needed for high flow oxygen. Additionally, a baby may require different masks or nasal attachment depending on their specific oxygen and breathing needs, and weaning progress.

Beeps

Pediatric cardiac intensive care unit rooms are full of medical machinery and monitors. Different patients may have different support needs and therefore different machinery involved.

Also, there are different brands of medical equipment. All of this is to say, that the beeps in your baby’s ICU room will not necessarily be the same as someone else’s beeps.

The lines, tubes and wires discussed in this post are connected or hooked up to different medical equipment or machines. Many of these provide vital signs, and various levels as information that your child’s medical team needs to know for their recovery. Other machines may provide more physical support to your child, such as for breathing, medications, or feeding.

Generally speaking, there are different beeps, alarms, and dings to notify your child’s medical team of different things. A machine or monitor may beep when it starts, pauses, stops, or completes a function. They may ding when there is an error. If a reading is too high, low, or out of range, there could be an alarm.

For example, when a feeding tube machine completes its feed volume, it might beep. When a blood pressure reading is out of range, it could beep. If a wire accidentally disconnects, it may alarm.

At first, it’s sensory overload. I found it to be an overwhelming nightmare the first couple of nights in my daughter’s ICU room.

After a month in the hospital, I didn’t even flinch with certain beeps, and others could still send me into a panic today.

Don’t hesitate to ask your nurse what this beep and that alarm mean. Over time, you may learn to recognize the different dings and distinguish between them.

Dropping the lines

All babies with Congenital Heart Defects, even those with the same exact defects, will have a different medical journey. Different CHDs necessitate different surgeries, and each recovery journey will be unique.

A baby’s age, surgery, health, complications, and more will impact how their recovery goes and how quickly they can drop lines. Hospital policies and medical team practices also vary, not everyone does things the same way.

By dropping lines, I mean when they no longer need a specific line (wire or tube) and can have it removed.

I’ll share our experiences for your reference, as long as you keep in mind this is our experience and will not be the same as your family’s experience.

If you want to know the expectations for your little one’s recovery, ask their nurses. If you have concerns, ask questions and get clarification. You are allowed to voice your concerns.

For my daughter’s first open heart surgery, at 3 days old, this is how she dropped her lines (for the ones I remembered to write down the date!).

- Foley catheter removed at 3 days post-op

- Central line removed at 7 days post-op

- Arterial line removed at 8 days post-op

- Pacing wires removed at 9 days post-op

- Extubated, breathing tube removed at 9 days post-op

- Off oxygen, nasal cannula removed at 13 days post-op

- PICC line removed at 18 days post-op

For her second open heart surgery, at 6.5 months old, this is how she dropped her lines.

- Foley catheter removed at 1 day post-op

- Extubated, breathing tube removed at 1 day post-op

- Central line removed at 3 days post-op

- Arterial line removed at 3 days post-op

- Left atrial line removed at 3 days post-op

- IVs (3) removed at 3 days post-op

- Chest tube removed at 4 days post-op

- Pacing wires removed at 4 days post-op

Scars from lines and tubes

I anticipated my daughter’s main zipper scar in the middle of her chest from her open heart surgery incision. This one, I knew to expect. However, I didn’t know to anticipate several other scars.

Many scars left behind from open heart surgery are due to the various lines and tubes. These lines are essential to a patient’s recovery, and they may leave behind their marks.

Wrapping up the wires

My jaw dropped the first time I saw the pediatric cardiothoracic ICU stacks. So much equipment, so many machines for such a tiny little one. Really?

It can be overwhelming, and crippling even to see your baby covered in so many wires and things. It can be really hard, and it makes sense that it’s not easy to see this and accept it.

However, I hope this guide helps you understand why they have these different wires, tubes, lines, and equipment and their importance.

Your child’s medical team is there to help them recover as quickly and as safely as possible, and these lines and equipment help them do this.

If you want to know what something is in your child’s room, don’t be afraid to ask! The nurses are a great resource. They helped us so much.

Not all babies having open heart surgery will require all of the discussed lines and wires, it depends on which surgery they have and their specific health factors. Also, hospital policies and processes can vary with how they handle certain patient care and recovery.

Save this post for reference while you’re in the ICU with your baby after open heart surgery.

Sources: Cleveland Clinic, Healthline, Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Journal of Perinatology, Nemours, Radiopaedia, Saint Luke’s, Verywell Health