A real-life nightmare with our 1-day-old newborn

We arrived at the front desk frantic… “our newborn baby was brought here by ambulance, where is she?!” The hospital lobby was eerily quiet since it was Saturday and the holiday season. Such a contrast to the cacophony symphony raging through my head.

It took forever to get us checked in, our IDs, covid vaccine cards, etc. She gave us badges that expired on Christmas. A little ping of (misguided) hope that maybe we’d be out of here by then? At this point, we still didn’t have exact clarity on her new diagnosis and the plan to address it.

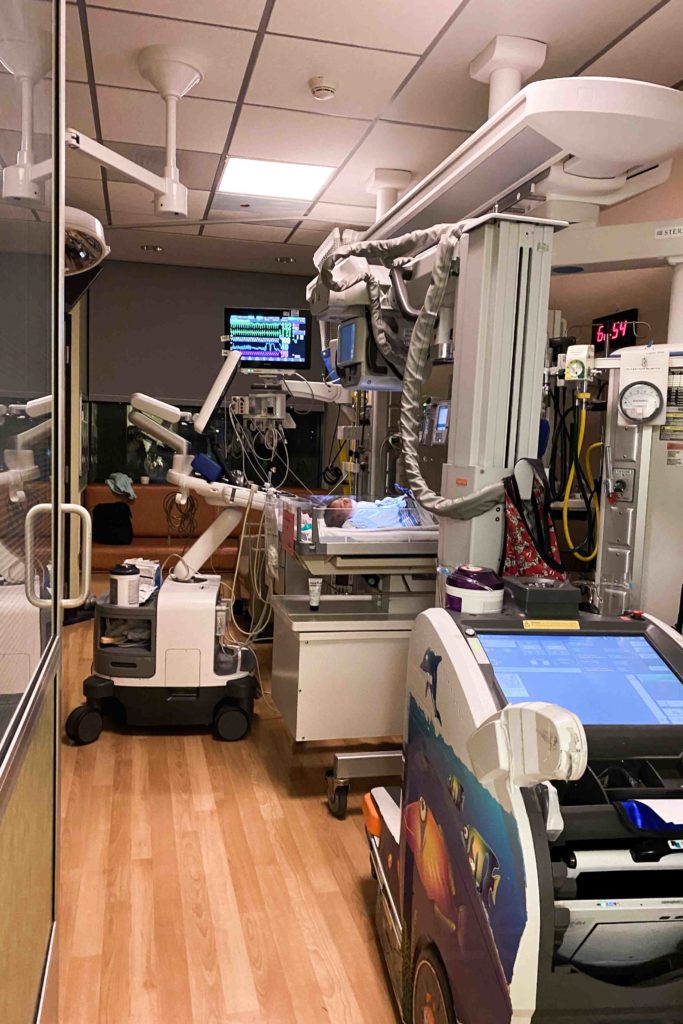

27 hours old: New hospital room in the cardiac ICU

Her report from this day reads, “She is critically ill due to risk of ductal dependent systemic blood flow requiring continuous monitoring and assessment.”

We raced upstairs, took a breath, pushed the buzzer, and walked through the double doors of the cardiac ICU. Déjà vu to when we toured the unit a couple of months ago. Then the NP was pointing out to us “a 5-month-old, a 2-year-old, a newborn” etc. since the setup with their beds is different by age and development. And I remember thinking to myself “oh a newborn, I can’t imagine, well that won’t be Isa.”

This time we entered the unit with a very different personal perspective that didn’t yet feel real and I didn’t like it. It was as if I was watching a show. Watching someone else be me, because this couldn’t actually be real. This was a nightmare.

We arrived at her room and there was a flurry of people all around her. But someone said, “nothing’s wrong, we are all just checking out how cute she is!” I tried to force a smile behind my mask, hiding my disbelief “what do you mean nothing’s wrong? Nothing is right. This is wrong, everything is wrong!”

Despite the challenging feelings, I also felt relief. The ICU team was so kind, upbeat, and on top of everything. I knew we had chosen the right place and felt confident having her in their care. Even so, I fought to reconcile this huge shift in plans and a new complex reality. Never mind the fact that I had only given birth about 30 hours ago. Emotion explosion.

Nurses, doctors, and technicians, from all different specialties, were revolving through her room. She had so many tests on this first day. They had to figure out her heart anatomy and defects to determine the best plan of action. Whether she needed any medications started now. And ultimately if she needed any procedures or surgery and how soon.

28 hours old: More discoveries, more complications?

She had a sacral dimple which could indicate a severe spinal cord issue or could be harmless. They found a cleft palate which could cause a range of challenges.

My spirits plummeted further. With such a combination of issues, they had to consider the possibility of a rare genetic condition. And they sent off a microarray test. Certain conditions could require a different plan or considerations.

I struggled to reckon how so many things could be so wrong with my seemingly perfect brand-new baby. At this point, outwardly, she still looked like a typical healthy newborn. She was not struggling at all or in any distress, she was still holding her own on room air (breathing as most of us do, no oxygen supplementation needed).

Tests and scans, however, told a very different story of what was going on inside. It was only a matter of time before she started to rapidly decline. They were racing the clock to figure everything out and make a plan before that happened.

You know when you get hit by a big wave, get knocked down, and have trouble getting back up because they keep coming? That’s what this first day felt like. We were living a nightmare.

29 hours old: Logistical and postpartum challenges

Another complication. With the holidays, more people were out. The chief of cardiac surgery had just left for a vacation to Colorado. We met with him previously and only felt comfortable with him specifically doing any surgeries necessary. His team was trying to conference with him remotely, update him on everything, and figure out the best plan. And try to find a way to get him back for Isa.

If you’ve given birth, you likely understand the strong urge to return home to your own private space and comforts to nurse your healing body. Instead, I occasionally found reprieve behind a curtain on a pull-out guest cot in my daughter’s ICU room.

So soon after giving birth, I’m leaking from everywhere, all over, and trying to keep up with it. Trying to sop up all my messes in a cold, sterile hospital bathroom. As I drenched mask after mask, COVID-19 numbers were climbing again.

Despite nursing my first two babies, I was not experienced with pumping. I scrambled to keep up with pumping as frequently as a newborn feeds and washing all the parts in between. Isa was not allowed to eat anything.

30 hours old: Navigating the medical unknown

Machines were rolled in and out of her room again and again. She had 2 x-rays (both chest) and 3 separate ultrasounds (renal, spinal, and cranial). She had another echocardiogram and EKG. With repeated echos, they were closely tracking any changes to her heart which can happen shortly after birth.

I had spent hours and hours getting to know AV canal defects (her prenatal diagnosis) forwards and backward. I knew this defect. I knew what to expect at birth, before surgery, the surgical details, and post-op. Now, however, I was floundering in a state of shock, flailing to grasp onto anything concrete. I didn’t understand her new complexity. I didn’t know what to expect. And I struggled in the unknown.

32 hours old: The first procedure

Nurses had trouble getting what they needed from her IVs, so they approached us gently about her first procedure, inserting a PICC line. After everything, it seems trivial now, but at that moment it felt so big.

A young anesthesiologist sat on the floor to talk us through it. She discussed the reasoning, the process, and the risks. I think she was trying to make us feel comfortable about it, but the approach worried us more… “it doesn’t seem like that big of a deal, but should we be more worried and questioning this?” We asked to discuss this with the senior anesthesiologist.

My husband signed the consent forms, our second set of consent forms stating seriously scary risks involving our newborn. I signed the first set but then didn’t want to sign anymore.

They proceeded with placing her PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter). She was put to sleep and on oxygen for a bit afterward. The PICC is a thin tube inserted in a tiny vein (usually arm, but as a newborn it went in her thigh) that goes all the way to the larger veins close to the heart.

Medications are delivered and effective more rapidly using a PICC line. They also used it to draw blood for various tests since they had trouble getting enough from her IVs. PICC lines have to be monitored closely, however, for infections and clots.

34 hours olds: Next steps

After her PICC line was in they decided they could not wait any longer, they had to start her on Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1). This would keep her alive. Yes, my newborn baby was being kept alive because of a medicine being delivered intravenously. What would have happened had we taken her home?

They needed to ensure her ductus arteriosus stayed open and this was the PGE1’s job. Of course, like any medication, this came with risks. Now they were monitoring her for apnea episodes (pauses in breathing).

As it got later, things slowed down. One of the cardiac surgeons came back around to discuss what they were seeing and thinking.

Her heart was much more complex than what was found prenatally. Her AV canal defect was unbalanced (typically more complicated) rather than the balanced (typically less complicated) prenatal diagnosis. At a high level, this meant one side of her heart was larger, the other side smaller.

In addition, she had multiple aorta defects. While they had a much better idea of her heart, they still were unclear about some things and their exact plan.

They were trying to determine whether they would have to take her down the single ventricle path, starting with the Norwood surgery. Or, if her anatomy would be able to eventually handle a full bi-ventricle repair. They would continue their conferencing on her case tomorrow.

Sitting in the unknown was agony. But exhaustion eventually consumed us and we dozed in and out of consciousness. I was in a haze setting alarms every 2 hours to pump, wash, rinse, and repeat.

Sometime in the middle of the night, I woke to the roar of a helicopter landing on the hospital roof. A real-life nightmare. Really. This can’t be real life, right? When am I going to wake up? The various machines and monitors constantly beeping in her room weren’t helping.

If only we had known…

If we had known about her additional heart defects ahead of time, all of this would have been planned. I would have had to be induced on a set date. We would have already picked a surgeon and hospital. I would have had to give birth closer to that hospital. Her first surgery would have been tentatively scheduled. And we would have made our plans around this.

It wouldn’t have been easy if it were planned, but I could have done without all the extra trauma of everything due to not knowing and having no plan.

This is CHD (Congenital Heart Disease).

I just finished reading your powerful and deeply moving account of your family’s journey with your newborn’s CHD diagnosis and the subsequent challenges you’ve faced. Your courage to share such personal and emotional experiences is truly commendable. Your narrative not only sheds light on the complexities of CHD but also offers solace and understanding to others navigating similar paths.

The way you’ve articulated the whirlwind of emotions—from the initial shock and fear to the moments of hope and resilience—struck a chord with me. It’s clear that your strength, love, and dedication to your daughter are boundless. Your story is a beacon of hope and a source of invaluable information for many families.

Please know that your words have made a profound impact. They’ve not only raised awareness about CHD but have also reminded us of the power of human spirit and the importance of community support during the most challenging times. Thank you for opening your heart to us, sharing your journey, and advocating for CHD awareness. Your family, and especially your brave little warrior, are in my thoughts.

I appreciate this extra thoughtful comment, thank you so much for reading and for your kind words.