The day my life changed: my baby’s AV canal defect diagnosis

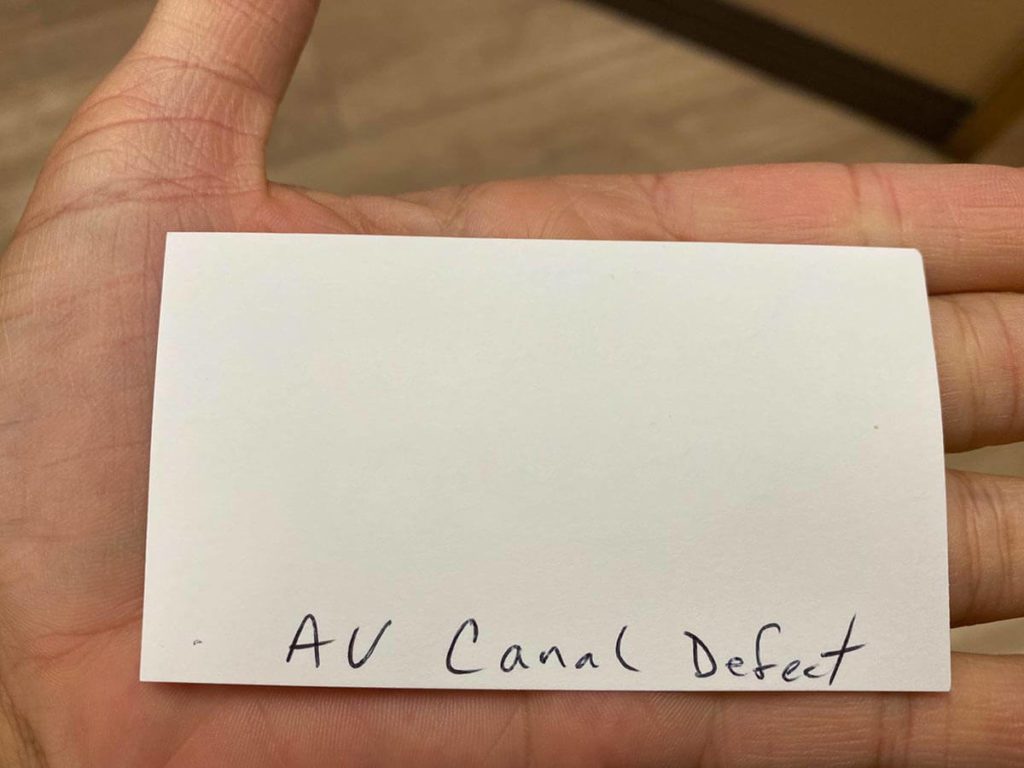

Only a little before my third trimester, a high-risk doctor handed me his business card and wrote the AV canal defect diagnosis on the back. He had discovered a large hole in the center, of my baby’s heart, which he suspected to be an AV (atrioventricular) canal defect.

From the very beginning, this pregnancy was starkly different from my previous two. However, there were no true issues or even red flags up until this point.

It actually felt a little serendipitous that they discovered it during my pregnancy rather than at birth or even later. Early discovery and intervention of congenital heart defects (CHDs) can make a big difference in successful management.

Let me take you through the story of when my daughter was first diagnosed with CHD.

Early pregnancy

This is my first pregnancy that I found out because of nausea. I was sick before I was even 4 weeks pregnant. With my previous pregnancies, I was nauseous here and there, but only over a few weeks. I had a subchorionic hematoma with my second that bled, but it didn’t cause any problems. Otherwise, they were uneventful.

With this pregnancy, when I went in for my confirmation and dating ultrasound, they found the baby to be measuring 2 weeks smaller than my dates. So they were not certain if it was a viable pregnancy. With successive ultrasounds they found the baby to be growing on track, but they changed my due date to 2 weeks later. I had a subchorionic hematoma, but it didn’t bleed and went away on its own.

My nausea persisted all day, every day until at least 14 weeks. After that my nausea was a little more sporadic but not completely absent. Finally, a little over halfway through the nausea mostly disappeared.

Early Testing

I opted for every non-invasive test made available to me. They were offered but not necessarily recommended to me as I had no specific reasons or special risk factors to warrant extra testing. However, since this pregnancy felt so wildly different from my previous ones, since I was a few years older, and since I have SIBO (a gut condition that can screw with your vitamin absorption among other things), I felt better getting all the tests. And, in general, I prefer having more information rather than less so I can plan.

All my tests kept coming back as low risk or no issues. The only thing that got flagged was my PAPP-A (Pregnancy Associated Plasma Protein-A – produced by the placenta) level which came back low. Low PAPP-A is associated with developing pre-eclampsia, early labor and lower birth weight. However, the likelihood of this happening is still very small. My midwives seemed unconcerned and only said that I would need extra monitoring as we got closer. I tried to remain unconcerned as well.

More testing can make you feel at ease, but it can also cause a lot more anxiety as you wait for results and consider all the what ifs. At this point, I was basically clear for everything, and the anatomy scan felt like the only remaining hurdle.

Middle pregnancy

We traveled to Greece as our last big trip as a family of four, and also visited family on the east coast. Everything was going smoothly. But we were away for almost a month, so I didn’t get in for my anatomy scan until I was just about 22 weeks.

During my anatomy ultrasound, the baby cooperated wonderfully. The tech seemed giddy about getting so many great pictures. She kept saying “beautiful” again and again. Only when she was trying to get the heart pictures, baby girl decided it was time to dance and move all about. The tech laughed, “she’s making me work for these ones!” But she didn’t seem concerned in the least about any aspect. Her heartbeat was normal and had been all along. All four chambers were visible and her heart looked to be pumping appropriately.

I met with my midwife directly after the anatomy scan. Everything looked okay to her at first glance, but she said an OB had to review them. And usually everything is fine, but sometimes they say they need more pictures or a closer look at a certain part.

“…we came to realize how common congenital heart defects are.”

Discovering a heart problem, an AV canal defect diagnosis

The afternoon after my anatomy scan, I got a call from my midwife. She said the OB who reviewed the images wanted to get a better look at the heart. My stomach dropped, of all the things, the heart.

I had to schedule a fetal echocardiogram with a high-risk MFM (maternal-fetal medicine) OB. A fetal echo is similar to an ultrasound, but they take a closer look at the baby’s heart and flow of blood to check if all structures have developed and are functioning normally.

Right away I was anxious about what could be. But I wasn’t able to get an appointment until 3 weeks away, and I knew I couldn’t obsess about it the whole time. Occasionally I allowed myself to Google reasons for a fetal echo, but I didn’t allow myself to go beyond that.

Our hearts are so critical and complex, and there is a wide spectrum of heart issues. It was pointless to worry and wonder over what it might be without further information. So I tried to tell myself he only wanted to see the heart better because baby girl was moving around so much during that part of the scan. Perhaps there were not enough heart pictures or they were too blurry.

Meditation must be working because I managed to stay relatively calm while waiting for my appointment.

On the day of my fetal echo, my husband got caught up at work and asked if I was fine going alone. And I said yes, because I was still unaware of any real reasons to be concerned, and was doing a good enough job not letting my head go down that path anyway.

The ultrasound tech asked me why I was sent in for the fetal echo, so I relayed the information about taking a closer look at the heart. But I didn’t have specific details beyond that.

After a bit, she said “Oh, I see why they wanted you to come…” and then stayed mostly quiet for the rest of the scan. Unnerving, to say the least. When she finished, she said the doctor would be in shortly. The wait was torture and not quick, my head was buzzing with what might be.

Eventually, the high-risk maternal-fetal medicine obstetrician came in. He was sensitive but frank about what they were seeing. A hole. Multiple holes. Malformed. Improper functioning. My baby’s heart was broken. Shook. Devastated.

“Why? What does this mean? Can she live like this?” He did some more scans and talked through exactly what it looked like to him. But I was in shock. So upset and overwhelmed, I couldn’t process it all so quickly.

He talked about several different implications for the rest of my pregnancy (tons more visits, delivering at a different hospital), for when she will be born (NICU), and thereafter (open-heart surgery). And ultimately said he needed to confer with the pediatric cardiologist, who would repeat the fetal echo and discuss everything with us in further detail.

He gave me his card and wrote his “AV canal defect” diagnosis on the back and his personal number. I thought, “If this special high-risk OB is giving me his personal number this really cannot be good.”

I left sobbing (and I’m not one to break down easily at all). Worst Friday of my life.

Thankfully both kids were in school, so I was able to go home and be by myself for a bit. I tearfully called my husband barely getting enough words out. He frantically tried to call the doctor and office for more information. The office called me back to set up appointments with a genetics counselor and with the pediatric cardiologist for Monday.

On his ride home, the doctor called us back to discuss details with both of us. We appreciated his candor and offer to call him anytime. But there were still details he couldn’t provide us that left a lot of questions unanswered. We would have to wait for Monday. It was going to be a long weekend.

We tried to distract ourselves with other things, keeping busy with the kids, going to Disneyland, and celebrating my husband’s birthday. But it was impossible to push the baby’s heart problem very far back in our minds.

Enter Google. They tell you not to Google anything, but we didn’t have that much self-control. And honestly, we’re glad we did. We were still missing a definitive diagnosis, but we searched for things related to AV canal defects and other comments the doctor made.

The more we read, the better we felt. We recognized this would be different than anticipated, and not an easy road, but it no longer felt completely hopeless.

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) are more common than we realized, though they can range significantly in severity.

Confirming the AV canal defect diagnosis

Monday finally arrived. We first met with a genetics counselor that unfortunately left us with no more information, and slightly more frustrated.

While they don’t know why many congenital heart defects occur, certain environmental, genetic factors, or chromosomal issues can be a reason. Most chromosomal disorders are random and not inherited. In contrast, genetic disorders are typically passed on from parents.

Addressing the baby’s heart condition could be more complicated if there are other issues that we don’t know about. Ideally, the doctors want as much information as possible to plan the baby’s care.

The only other test I could do at this point was an amniocentesis. This test is the most concrete way to test for chromosomal abnormalities, however, it’s invasive. Before 20 weeks pregnant there is a very small chance of miscarrying. After 24 weeks, the risk changes to going into preterm labor.

Since I had already done all the non-invasive testing with multiple reports of low or no risk, to us, the risks of doing an amnio were not worth it. But of course, this left us with still some unknowns.

In the afternoon we met with the pediatric cardiologist. A tech did another fetal echocardiogram while the cardiologist watched, took notes, and confirmed details. She was very transparent and personable, and quickly put us at ease. After the scan, we discussed all the details in the office.

First, she talked us through the basic anatomy and functions of a typical healthy heart. And confirmed our baby’s AV canal defect diagnosis (also known as an Atrioventricular canal defect, atrioventricular septal defect, AVSD). Hers is a complete atrioventricular canal defect (CAVC), as opposed to the less severe but less common partial/transitional atrioventricular canal defect. However, it is balanced as opposed to unbalanced, which is a positive when it comes to repair.

AV canal defect is a hole or multiple holes in the middle of the heart. Since they are right in the center, they interfere with both the lower and upper chambers and the valves. This causes oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood to mix, leaking, and overall the heart has to work much harder than a healthy heart.

It is extremely rare for a baby with an AV canal defect to be able to live without having it repaired. So they must have open-heart surgery, typically within their first year of life to repair the defect.

The pediatric cardiologist explained everything and answered our long list of questions. I actually thought it was a partial AV canal defect, not complete. Which means it is a little worse than I realized. However, thankfully, we left the appointment feeling better than the last several days. It was a relief to have a definitive diagnosis and a better understanding of what to expect.

Light and hope after the AV canal defect diagnosis

While the AV canal defect diagnosis shocked us, we came to realize how common congenital heart defects are. And while our baby’s is not the most common (only about 2,000 babies per year in the U.S.), it is common enough and they have made enough advancements over the last couple of decades that the outlook is good.

Nothing is guaranteed, but with early detection and planning, we have hope that our baby girl will be just fine after her open-heart surgery.